When I moved to Montreal, it was a vibrant, multilingual metropolis. Now François Legault is waging war on English and on the cosmopolitanism that makes it Canada’s greatest city.

hen François Legault is in downtown Montreal, he doesn’t like what he hears. Quebec’s premier works from an office on Sherbrooke Street, right in the heart of the city, only a few blocks from the mountain that gives Montreal its name and directly across the street from the Roddick Gates, the grand, columned entrance to McGill, Quebec’s most prestigious university. And it is the sound of English, not French, that often dominates here.

The government did bend on the tuition policy, a little bit. In December, Minister of Higher Education Pascale Déry announced tuition would rise to only $12,000, instead of $17,000. But she also announced that 80 per cent of out-of-province and international students would have to reach an intermediate level of French proficiency by graduation. Universities that didn’t achieve the target would be fined.

Since I was a kid, I knew I would live in Quebec. Maybe the seed was planted when I started Grade 1 in French immersion in 1988 and learned that “airplane” in French is “avion”—a fact I found fascinating and memorable as a six-year-old.

It was into this world that François Legault came of age. Born in 1957, he was raised in a francophone family in the primarily anglophone enclave of Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, on Montreal’s West Island. His childhood and adolescence put him on the frontlines of the Quiet Revolution; even teenage hockey matches were divided by language. As a teenager, he and his friends grew tired of seeing the businessmen reading the English-language, a separatist newspaper.

Months after the CAQ was founded, it merged with the flagging ADQ, bringing under its wing that party’s conservative, culture-war bona fides. Right from the beginning, the new party made the idea of French in peril a core tenet of its brand. That simplistic messaging exploited many people’s longstanding fears, but the reality is that French was thriving. The Quiet Revolution really had succeeded in flipping the linguistic polarity.

It was with that soaring approval rating that his government introduced, in May of 2021, its next volley: Bill 96, an update to the original language charter, which deepened and expanded its reach, relying mostly on simplistic claims about the decline of French. The bill was crafted based on the findings of Canada’s 2016 census, which had, in fact, marked a slight decline in French use in Quebec. Then the 2021 census data came out—and it hit the language debate like a shot of nuclear fission.

Jean-Pierre Corbeil is a sociologist at Université Laval and part of an emerging academic movement pushing back against the narrative of French decline. “By focusing on the results of the 2021 census, almost 40 years of significant progress in the development of the presence and use of French as a common public language have been eliminated from the discourse,” he writes in his new book,In fact, he argues the opposite. Bill 101 pushed many anglophones out of the province.

since the cost of tuition doesn’t come close to paying for their studies. But it’s true that a small portion of out-of-province students have long enjoyed an amazing deal in Quebec. Prior to the new policy, an arts or science degree at McGill or Concordia would cost them roughly as much as they’d pay elsewhere in Canada. Degrees in some programs, however, including law, medicine and engineering, were much, much cheaper.

Last December, I visited the home of Serge Sasseville, the city councillor for the Peter-McGill district, which includes both McGill and Concordia universities, as well as Dawson College. His district is the antithesis of the CAQ’s base of support. As of the 2016 census, more than 16,000 of its 33,000 residents identified as visible minorities, more than 4,000 were recent immigrants and more than 11,000 spoke only English. More than 700 spoke neither official language.

Canada Latest News, Canada Headlines

Similar News:You can also read news stories similar to this one that we have collected from other news sources.

Quebec's New French Revolution - Macleans.caWhen I moved to Montreal, it was a vibrant, multilingual metropolis. Now François Legault is waging war on English and on the cosmopolitanism that makes it Canada’s greatest city.

Quebec's New French Revolution - Macleans.caWhen I moved to Montreal, it was a vibrant, multilingual metropolis. Now François Legault is waging war on English and on the cosmopolitanism that makes it Canada’s greatest city.

Read more »

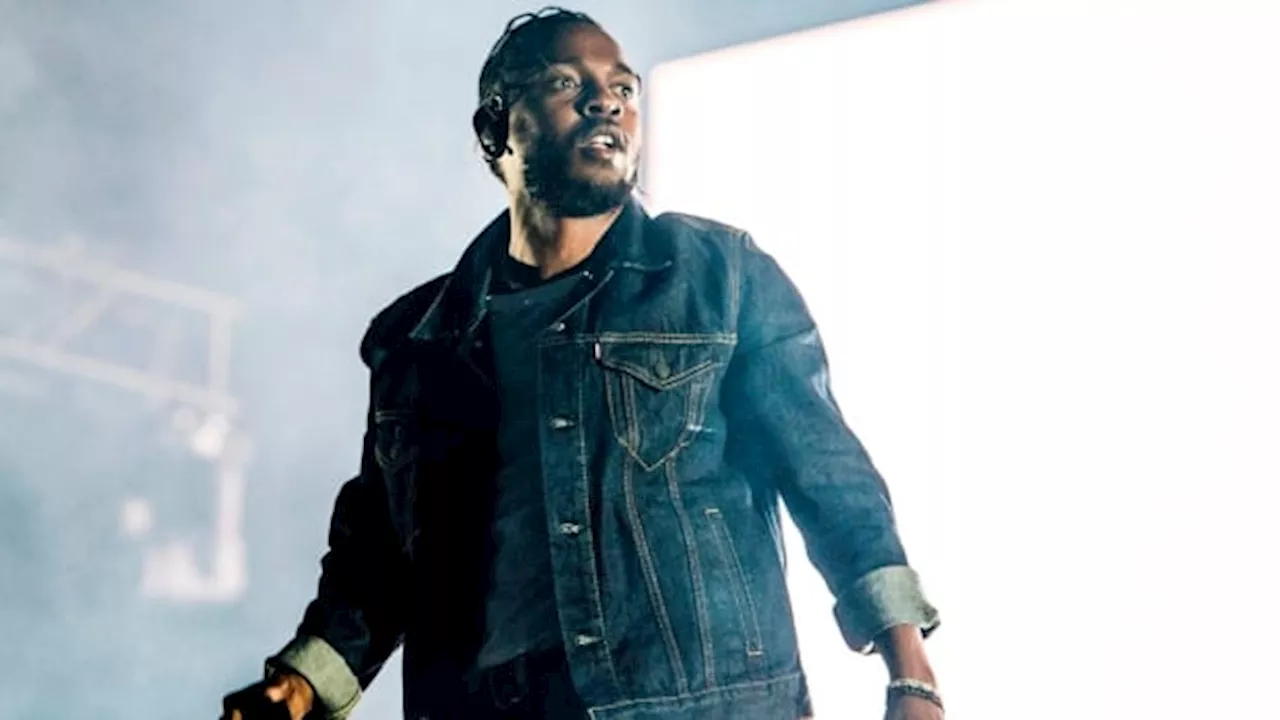

How bad does Drake look after Kendrick Lamar's diss track Euphoria?Kendrick Lamar performs during the Festival d'ete de Quebec in Quebec City, Canada.

How bad does Drake look after Kendrick Lamar's diss track Euphoria?Kendrick Lamar performs during the Festival d'ete de Quebec in Quebec City, Canada.

Read more »

Quebec to spend $603M to help French remain vital in the provinceCoalition Avenir Quebec Minister of the French Language Jean-François Roberge speaks at a news conference, Thursday, Nov. 23, 2023 at the legislature in Quebec City. St-THE CANADIAN PRESS/Karoline Boucher

Quebec to spend $603M to help French remain vital in the provinceCoalition Avenir Quebec Minister of the French Language Jean-François Roberge speaks at a news conference, Thursday, Nov. 23, 2023 at the legislature in Quebec City. St-THE CANADIAN PRESS/Karoline Boucher

Read more »

Quebec unveils $603 million five-year plan to protect French languageMONTREAL — Quebec is investing $603 million over the next five years to counter what its French-language minister describes as the decline of the French language in the province.

Quebec unveils $603 million five-year plan to protect French languageMONTREAL — Quebec is investing $603 million over the next five years to counter what its French-language minister describes as the decline of the French language in the province.

Read more »

Quebec unveils $603 million five-year plan to protect French languageMONTREAL — Quebec is investing $603 million over the next five years to counter what its French-language minister describes as the decline of the French language in the province.

Quebec unveils $603 million five-year plan to protect French languageMONTREAL — Quebec is investing $603 million over the next five years to counter what its French-language minister describes as the decline of the French language in the province.

Read more »

Quebec unveils $603 million five-year plan to protect French languageMONTREAL — Quebec is investing $603 million over the next five years to counter what its French-language minister describes as the decline of the French language in the province.

Quebec unveils $603 million five-year plan to protect French languageMONTREAL — Quebec is investing $603 million over the next five years to counter what its French-language minister describes as the decline of the French language in the province.

Read more »