Argentines vote for a new president on Oct. 22, and one libertarian hopeful says he will take a chainsaw to the status quo if elected. Critics fear their rights and social safety net will get shredded

Before an outsider libertarian candidate shifted the axis of’s presidential elections, tattoo artist Jonathan Aguirre held his little girl Olivia in his arms.

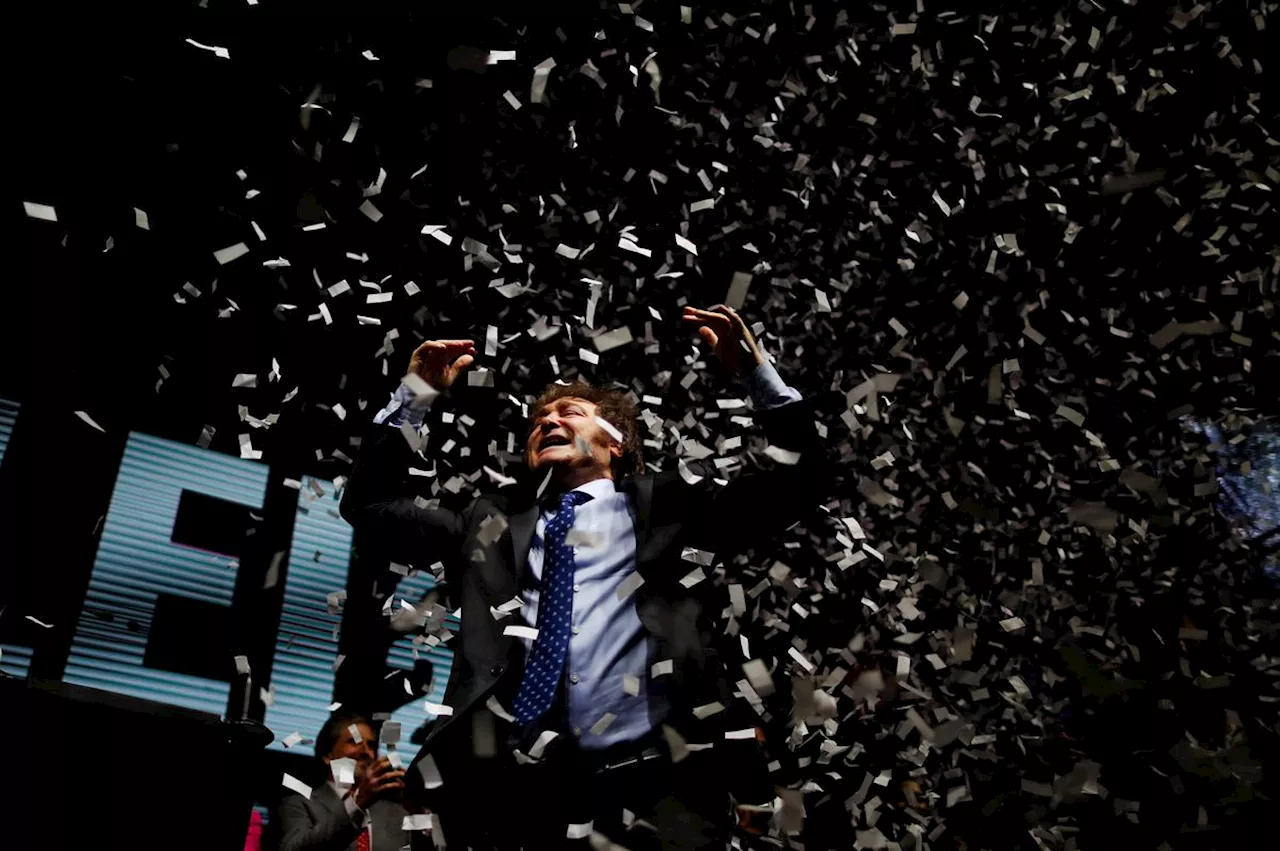

The Sun of May, centrepiece of the Argentine flag, shines above the crowd at a Milei primary rally in August.On this windy night in August, he was on the cusp of a stunning presidential primary victory that revealed just how hungry Argentines are for a change: By winning almost 30 per cent of the vote, he edged out the other two traditional coalitions of left and right.

Mr. Milei fits into the narrative of right-wing populists gaining ground around the globe. Comparisons abound with Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s now-ousted far-right president, although of course there are specific differences between the three. Mr. Milei, a self-described “anarcho-capitalist,” touts and relishes the similarities, in particular around a shared desire to quash socialism in their respective societies.

The media has pumped out stories on his five English mastiffs, four named for conservative economists, and clones of a first and beloved dog called Conan. He’s lambasted the Pope, a fellow Argentine, supports legalizing the sale of human organs, and is stoking denialist rhetoric around the atrocities committed by the last military dictatorship. When a female rival called him a “pussy cat” rather than the “lion” he purports to be, the fan fiction rolled in. Taxes are theft, he says.

There was also some measure of admiration – that the people who were supporting Mr. Milei appeared to be on track to do something they had not been able to make happen out of the ashes of 2001, when people occupied banks, factories, and established alternative economies that enabled them to survive.

Inflation in Argentina has made it hard for pensioner Simona Alegre, 65, to support the six grandchildren who share her home in working-class Villa Fiorito. ‘I was a Peronist my whole life, and I thank them,’ she says, but now she is unsure who to vote for to make things better.Mr. Milei has strong support in the poor northern province of Salta, where he got more than half the primary vote in August.

The “they” Mr. Ferreira is referring to are his neighbours in Villa Fiorito, a working-class municipality on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. Before he started his delivery shift, he was handing out flyers in a plaza in Fiorito, trying to woo people to the messages of libertarianism. Mr. Ferreira’s own trajectory offers a window into some of the conditions that created a climate for Mr. Milei.